MUSEUM DUNIA MAYA DR IWAN S.

Dr IWAN ‘S CYBERMUSEUM

THE FIRST INDONESIAN CYBERMUSEUM

MUSEUM DUNIA MAYA PERTAMA DI INDONESIA

DALAM PROSES UNTUK MENDAPATKAN SERTIFIKAT MURI

PENDIRI DAN PENEMU IDE

THE FOUNDER

Dr IWAN SUWANDY, MHA

WELCOME TO THE MAIN HALL OF FREEDOM

SELAMAT DATANG DI GEDUNG UTAMA “MERDEKA

The Driwan’s Cybermuseum

(Museum Duniamaya Dr Iwan)

Showroom :

The Driwan Dai Nippon War’s book

(Buku Karang Dr Iwan “Perang Dai nippon)

Showcase:

The Dai Nippon Occupation Java ‘s Postal and document History 1942

Frame One:

Introductions

1.I have the complete collection of postal and ocument history during Dai Nippon Occupations Java Idsland 1942-1945, chronology day per day from the Capitulation day on March,8th.1945 to August,17th,1945(2605) ,also until The Japanese Army back Home to their homeland Dec.1945 but the Dai nippon revenue still used by Republic Indonesai until 1947.

2. Now I only add the 1942(2602) Collections, and if the collectors want the look the complete collections ,not only from Java island but also from sumatra Island, please subscribe as the blog premium member via comment,and we will contack you via your airmail. We will help you to arranged the very rare and amizing collections of Dai Nippon Occupations Indonesia postal and document special for you.

3.I had add in my block the articles odf Dai nippon war from all east asia countries, many collectors and friend asking me to edited that all information in one book, and now I have finish that amizing book.

4.Not many Historic Pictures durting this period, if we found always in bad condition and black _white as the book illustrations, I hope someday the best colour pictures will exist to add in the book.

5.This book is the part of the Book :”THE DAI NIPPON WAR”

6. My Collections still need more info and corrections from the collectors of all over the world,thanks for your partcipatnt to make this collections more complete.

Jakarta, April 2011

Greatings From

Dr Iwan Suwandy

Table Of Content

Part One:

The Dai Nippon war In Indonesia

1.Chapter One :

The dai nippon war In Indonesia 1942.

2.Chapter Two:The Dai Nippon War In Indonesia 1945

Part Two.:

The Dai Nippon War In Korea

Part Three:

The Dai Nippon war In China

Part Four :

The Dai Nippon War In Malaya Archiphelago ,Malayan Borneo and Singapore

Part five :

The Dai Nippon War In Burma and Vietnam

Part six:

The Dai Nippon War Homeland Preparation

Part seven:

The Dai Nippon Pasific War

__________________________________________________________________________

DAI NIPPON WAR PART TWO: CHAPTER ONE

“THE DAI NIPPON WAR IN INDONESIA 1942”

1.Dai Nippon War in West Papua

Hamadi bay was once an ally of the first soldiers landed, which then goes and makes the defense barracks in the hills Mac Arthur (ordinary Papuans call Makatur hill), located in the hills Sentani. If the current travel there by car takes between 45-60 minutes from Jayapura, I can not imagine how long the first Allied troops reached the hill in one week

Jend. D. MacArthur and Major General HH Fuller; commander Div # 41, shortly after landing on the beach Hamadi

Yes, hills Ifar Mountain, where the headquarters of the Pacific Southwest of the Mandala Command led by General MacArthur is located, held approximately 2-3 days after U.S. forces completed the 4-day military operation to master the three Japanese air base in Sentani area.

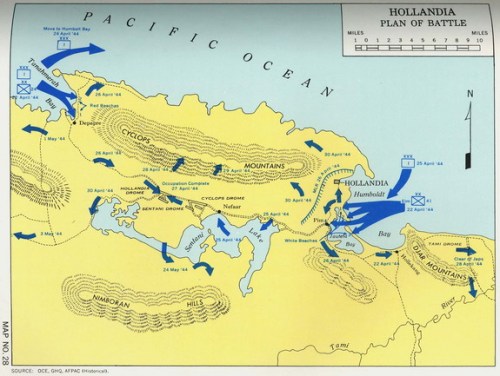

Allied military operation to seize Jayapura (then named Hollandia) and Sentani from the Japanese took place on 22 to 26 April 1944 and known as Operation Reckless, and usually called simultaneously with Operation Persecution run concurrently with the target of Aitape, 200km in east of Jayapura, Papua New Guinea in the region now.

I saw the scholar never any attempt to study these events, unfortunately, the information obtained the IMO rather vague and less specific about the Battle of Hollandia itself. So, this is a short version .

3.1943.

Allied counter-attack:

Mid-1943, the Pacific war had passed the turning point where the original Japanese in the offensive has turned into the defensive.

4. 1944

Purple arrows: invasion of the Allies until February 44, controls the eastern tip of New Guinea, and will jump straight to Madang to Wewak Hollandia

The absence of orientation in a long term war, and the leaking of secret code the Japanese military, played a role in the series of Japan’s defeat in the outer perimeter of the Japanese defense line in the Bismarck Archipelago, the Solomons and the Huon Peninsula in the east end of New Guinea, while Rabaul, Japan’s leading bastion in the Pacific practical been isolated. Therefore the Japanese began to rewind the perimeter defenses in the north coast of New Guinea with the front line around Wewak, Madang, Hollandia, which is built into the main military base for the transit of troops and cargo from the sea, also the center of the new air force (moved from Rabaul).

Toward Hollandia:

Meanwhile, the Allied side (in this case General MacArthur and the Southwest Pacific Command Mandala lead) looking at Hollandia as a strategic stepping stone that will bring him and his soldiers 800km to the main targets in the Philippines. Leap frog strategy to seize Hollandia also means fighting in a place chosen the U.S., because Japan expects the Allies landed between Madang and Wewak, where the Japanese hold three infantry divisions of the Army # 18-automatic-insulated with Hollandia landings.

Tuk predict the failure of Japan to the Allied attack Hollandia Hollandia due to their calculations that are beyond the reach of allied fighter planes of their leading pengkalan in Nieuw Guinea (Nadzab). This is certainly easy to be overcome by utilizing the support Allied aircraft carriers and planes within the latest travel far. However, operations planners decided to occupy the Aitape also because there are air base that can be used Tadji allies, taking into account the Hollandia will be stubbornly defended. Moreover, because Japan is also building two air base in Wakde and Sarmi, over 200km southwest of Hollandia.

APRIL,1944

Operation target:

In the attack on Hollandia, in addition to the city and sea port, which became the main target is the three Allied air base in Sentani area, 40km west of Hollandia, which each called Lanud Sentani, Cyclops and air base air base Hollandia (Lanud Tami, the fourth, are near the border of RI-PNG now). Targets in Sentani is clamped with a planned simultaneous attack through the amphibious landing of two directions, ie from the direction of Humboldt Bay (Gulf Yos Sudarso now) and the Gulf Tanahmerah. The military operation is scheduled to take place on April 22, 1944.

Allied strength.

Air power in this attack is the U.S. Air Force # 5, Task Force 73 (land-based naval aircraft), Australia AU components, Task Force 78 (escort aircraft carriers of the Fleet # 7) and Task Force 58 (the major carriers of Fleet # 5, loaned by Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, commander of the Pacific Ocean to the MacArthur Mandala tuk this attack).

Allied fleet was divided into Task Forces 77.1 (group assault center. Objective: Bay Tanahmerah); Task Force 77.2 (western assault group. Objective: Humboldt Bay); Task Force 77.3 (east assault group; Target: Aitape); Task Force 74 ( A bodyguard unit), Task Force 75 (bodyguard unit B) and several other Task Force (77.4-7) that serves as a reserve force and controlling the landing. Together with carriers, a total of 217 Allied ships deployed in this mission.

As the spearhead of the attack on Hollandia was the Task Force Reckless: two infantry divisions of the Corps # 1, # 6 U.S. Army; Infantry Division # 24 (Gulf Tanahmerah target) and the Infantry Division # 41 (Humboldt Bay target); while Aitape be occupied by Cluster Persecution task, namely Infantry Regiment # 163 of Divif # 41. Total of all ground forces numbered nearly 50,000 soldiers.

From H to H plus minus.

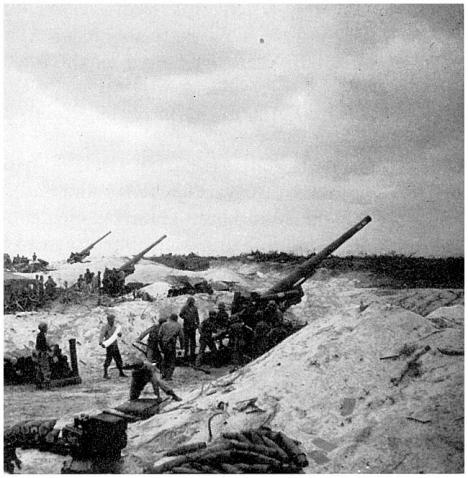

Beginning in late March, the Allied air forces conducted repeated bombings against all Japanese air and naval bases along the northern coast of Papua, to the Arafura Sea, also get to Kep. Caroline and Palau. In Hollandia course, this preemptive strike to destroy Japanese planes 300an per 3 April. Meanwhile, the Allies continued to deceive the Japanese with a variety of tactics so that Japan can not predict where the next invasion would be directed.

On 17 and 18 April 1944, a convoy of ships began to move from their base at the end of New Guinea. Of Goodenough Island brings Div # 24, and from Cape Cretin brings Div # 41. While the Task Force set out from Finschhafen Persecution. 20 April, the convoy headed north to play Admiralties islands, so as not observed from Hansa Bay coastline. From the north Admiralties convoy moving directly toward the target. 12km from the coast between Hollandia and Aitape, attacking the eastern breakaway group to execute Operation Persecution.

On the day 0130AM, 20 miles off the coast between the two bays target, a convoy of the remaining breakaway: group attacking the middle toward Humboldt Bay, while the western attack groups and task forces operating from headquarters + reservists to the Gulf Tanahmerah. 0700 planned landing simultaneously on the morning after a series of shore bombardment, and Reckless Operation officially begins.

Allied fleet movement from base to target

In the Gulf Tanahmerah, landings performed Infantry Division # 24 at two locations codenamed Red Beach 1 and 2. Due to take into account that the main Japanese force will be concentrated to maintain Hollandia (who invaded from Humboldt), the largest landing troops, including logistics and staff will put ashore here. But conditions in the field was not in accordance with the interpretation of aerial photographs of the operations planner. At Red Beach 2 there is no way to Red Beach 1, so that troops, equipment and supplies are piling up on the beach should be taken back to the small boats to Red Beach 1.

APRIL,25th.1944

LST at Red Beach 2

Meanwhile, from Depapre (Red Beach 1) to the target in Sentani turns out there is only a path that can not pass a vehicle up to much, even by tanks, there’s no way made in Japan as predicted. Therefore, troops from Div # 24 should move forward with a walk, bringing logistics chain. Meanwhile supplies, headquarters staff (some of which have gone down), reservists and support units are still on the ship diverted to Humboldt Bay. So is the status of forces transferred to the main bat Div # 41 which moves more smoothly.

That same morning the leading forces (Yon # 1) has reached Maribu without a fight, there are only remnants of the Japanese troops who fled equipment. Next to the Paipou. Jangkena, Waibron, Dazai (Dosai now) before reaching Sabron next day. In Sabron Japan had no resistance to withstand forces up to date 23. While the battalion # 1 opens the road. Battalion # 2, # 3 and the remaining forces preoccupied with carrying ammunition and rations in sequence, a walk from the beach until the troop leader (about 12 miles). These logistical problems inhibiting the movement of troops until the 25th, because the distance that must be taken to drain the logistics to forces that also more and more, not to mention the rain always falls. 25 April, where forces had received opposition leader again in Dejaoe River, about 3500 troops already assigned to just to bring the logistics alone. Even with all the limitations, the next day (26), Yon # 1 has been successfully mastered Lanud Hollandia, and some logistics successfully deployed using the aircraft in Dazai. Meanwhile the vehicle from both ends also have to get through some of the road. That day, around Weversdorp, a unit of Div # 24 was able to make contact with the unit from Div # 41.

The movement of Allied ground forces

The beach is very narrow

In Humboldt Bay, the landing Div # 41 conducted at four locations codenamed White Beach 1-4. Here also the landing went smoothly and very few get resistance. The problem faced is also the same, namely the beach is too narrow to accommodate the cargo ship-landing craft, and endeavor to build a road from the beach to the highway Pim-Hollandia.

As soon as all the troops landed, the two regiments from Div # 41 split. # 162 Regiment moved to the town of Hollandia, while the Regiment # 186 moves toward Sentani. Pancake Day is also the hill and the hill Jarremoh (complex transmitter Polimaq now) can be controlled, and the date of 23 noon, the city of Hollandia, had fallen into the hands of U.S. troops.

On the other hand, forces that led to Sentani experienced little difficulty because of heavy rains that make roads full of puddles, also some sporadic resistance from Japanese forces. U.S. troops also could be saving rations and ammunition because on 23 midnight, a single attack Japanese fighter planes at White Beach, a chain explosion that destroyed 60% of U.S. logistics and ammunition up to H +1.

On the 24th afternoon, U.S. forces have control of small natural dock in koyabu (Yoka) which can be used for amphibious assault. 25 am, 2 companies of the 1st Battalion started the movement of amphibians through the village towards the lake Sentani Nefaar (Netar now), followed by the rest of the Battalion 1 in the afternoon. 25 afternoon, 3rd Battalion moving by land (Sentani lake side) has joined. On 26 morning, leading the troops that day divided by two and also controlled air base Cyclops (10:40 hours) and, after passing through the village Ifaar, controlled air base in Sentani (11:30). The entire target declared safe an hour later without combat means, and when the dusk, was able to make contact with a unit of Division # 21.

JUNE,1944

Allied troop movements to the phase of “clean”.

After all the main targets declared operations is achieved on 26, then proceed with the operation control of the area around and clean them from remaining Japanese forces. In the days that followed U.S. forces move to master the south side of Mount Cyclops (the Southwest Pacific Command headquarters Mandala later built), Tanjung Suaja (Tanjung Ria), Hollekang (Holtekamp now), Goya (Koya) and Tanjung Jar, then mastered Lanud Tami. This air base was later used as a bridgehead tuk air transport logistics of troop ships bound for the difficulties in the Sentani area ration. U.S. troops also spread and establish outposts to the Marneda, Gulf Demta, even Genyem. The “clean-up” is completed by June 6, 1944.

Survivors:

Unexpected ally, the attack on Hollandia did not get resistance from the Japanese meaning. In addition to its element of surprise, this is also due to the limited time and resources owned by the Japanese to move a significant ground combat element to the Hollandia or reinforce existing forces. As of 22 April 1944, from about 11,000 Japanese troops in Hollandia, 500an only just ground forces of anti-air attack unit. The rest comes from the air force, navy and other supporting units.

Japanese forces retreat

22 April morning, which took over the command of Major General Inada of Japan in Hollandia, prepare their best opposition and still managed to coordinate the resistance in Sabron. But most of the troops immediately fled to the mountains shortly after the U.S. ships do the bombardment, and in that night, Major General Inada already ordered retreat. Without the supplies which are all stored in the vicinity of Humboldt Bay, the Japanese retreated toward Genyem, where they held a farming project. April 30, about 7,000 Japanese troops in 10 groups to organize themselves, without a map and supplies are limited, began a long march toward Sarmi through the path in the woods; some one to Demta, 25km to the west coast village Depapre. Because the insulation of U.S. troops, stray, hunger, injury, fatigue and illness, the trip becomes deadly, and only about 7% up in Sarmi. In total, only about 1000an those Japanese soldiers who survived the invasion of Hollandia. 3300an people were killed or found dead, and the remainder (almost 7000) is lost. On the other hand, only 124 U.S. troops are killed, 1057 wounded and 28 missing.

Hollandia, after the invasion.

After the successful invasion, the Allies then build a variety of military facilities, especially for the Seventh Fleet, which spread from the Gulf to the Cape Suadja Tanahmerah. The entire military installations in the Hollandia and the surrounding area was then given an alphabetic code “Base G”.

The flurry of U.S. troops in the port that is being built

Jend. D. MacArthur moved his headquarters Mandala Command Southwest Pacific from Brisbane to Hollandia in August 1944, on a hill now called Ifar Mountain, about 4km Cyclops northern air base. Together with co-headquartered in SWPA headquarters also commands underneath al: Armada # 7, AD # 6, # 8 Army, Allied Force and Allied Land Army.

Later in the war, Hollandia became the starting point for subsequent Allied invasions into P. Wakde, P. Biak, P. Numfor, Sansapor, and P. Morotai, until landing in P. Luzon, Philippines. Meanwhile AD # 18 Japanese were locked around Wewak result of this operation, was defeated at the end of August.

5. 1945.

DECEMBER ,1945

After the war.

Along with the end of World War II, in December 1945 to sell all U.S. military facilities in Hollandia, the Dutch East Indies government, which then pass it to the government of Indonesia after surgery Trikora (subsequently named Soekarnopura Hollandia, and Jayapura). Most of the military facilities are built MacArthur’s troops and fell into the hands of Indonesian military, especially to the military command Trikora XVII, including mako complex in Ifar Mount MacArthur, Sentani, who is now a Parent Regiment Kodam (Rindam), and the Regional Military installations around Kloofkamp, including complex Kodam long. Allied landing site at White Beach 1 & 2 into Navy housing complex, while the air base used AFAIK Hollandia AU base in Jayapura (without aviation facilities). Fleet # 7 As for the port and air base in Sentani (Sentani airport now) functioned as a general entrance gate to Jayapura. There are also buildings controlled by civilians and was switching function or torn down. Only Lanud Cycloops which I can not be sure no place for them. Although there is a place which I suspect is based on the approximate position of the map and some of the Quonset hut-building half-cylindrical metal assemblies that characterized the construction of U.S. military engineer corps legacy of World War II-era near there.

As for heritage buildings is not like the carcasses of so many military vehicles scattered around the landing site, is up for sale as scrap metal by local communities. While the rest of the bombs, mortars and bullets that do not explode during the Allied attack, there is no end to be found and used as raw material for bomb fishing by local communities. BTW, a drum of fuel supertebal USAAF still remains as a drum of water I use in my home now.

MacArthur Monument at Mount Ifar now. .

Encore:

A monument on the beach Hamadi events marking the Allied landings, while the other Abepantai monument marking the arrival of Japanese troops two years earlier. Both, along with dozens of Quonset hut that is still scattered throughout the city, and MacArthur in the complex Rindam Monument, a reminder of the war that never passes Jayapura, whose story is more vague and forgotten. There are even official information is false, too! So, while there has been no more wars, let us celebrate life

Teluk Hamadi ini dulu merupakan daerah awalnya para tentara sekutu mendarat, yang kemudian berjalan dan membuat barak pertahanan di bukit Mac Arthur (orang Papua biasa menamakan bukit Makatur), yang terletak di atas perbukitan Sentani. Jika perjalanan ke sana saat ini dengan kendaraan memakan waktu antara 45-60 menit dari Jayapura, saya tak terbayangkan berapa lama tentara Sekutu dulu mencapai atas bukit tsb. satu minggu.

Jend. D. MacArthur dan Mayjen H.H Fuller; panglima Div #41, sesaat sesudah mendarat di pantai Hamadi

Jend. D. MacArthur dan Mayjen H.H Fuller; panglima Div #41, sesaat sesudah mendarat di pantai HamadiYa, bukit Ifar Gunung, tempat markas Komando Mandala Pasifik BaratDaya yang dipimpin Jenderal MacArthur terletak, dikuasai sekitar 2-3 hari sesudah pasukan AS menyelesaikan 4 hari operasi militer untuk menguasai 3 pangkalan udara Jepang di daerah Sentani.

Operasi militer Sekutu untuk merebut Jayapura (saat itu bernama Hollandia) dan Sentani dari pihak Jepang ini berlangsung tanggal 22-26 April 1944 dan dikenal dengan nama Operation Reckless, dan biasanya disebut secara simultan dengan Operation Persecution yang dijalankan secara bersamaan dengan target Aitape, 200km di sebelah timur Jayapura, di wilayah Papua New Guinea sekarang.

Saya melihat pernah ada usaha Bu Enny untuk mempelajari peristiwa ini, sayangnya, informasi yang didapat Bu Enny IMO agak kabur dan kurang spesifik tentang Battle of Hollandia itu sendiri. Jadi, ini versi singkat dari saya.

*sok tahu mode: ON*

Serangan balik Sekutu:

Pertengahan 1943, perang Pasifik telah melewati titik baliknya dimana Jepang yang semula di pihak ofensif telah berganti menjadi pihak defensif.

Panah ungu: serbuan pasukan sekutu hingga Februari 44, menguasai ujung timur Nieuw Guinea, dan akan melompati Madang hingga Wewak langsung ke Hollandia

Panah ungu: serbuan pasukan sekutu hingga Februari 44, menguasai ujung timur Nieuw Guinea, dan akan melompati Madang hingga Wewak langsung ke HollandiaKetiadaan orientasi dalam suatu perang jangka panjang, dan bocornya sandi rahasia militer Jepang, turut berperan dalam rangkaian kekalahan Jepang di garis terluar perimeter pertahanan Jepang di Kepulauan Bismarck, Solomons dan Semenanjung Huon di ujung timur Nieuw Guinea, sementara Rabaul, benteng terdepan Jepang di Pasifik praktis sudah terisolasi. Karena itu Jepang mulai memundurkan perimeter pertahanannya di pantai utara Nieuw Guinea dengan garis depan di sekitar Wewak-Madang, dimana Hollandia dibangun menjadi pangkalan militer utama untuk transit pasukan dan kargo dari laut, juga pusat kekuatan udara yang baru (pindah dari Rabaul).

Menuju Hollandia:

Sementara itu, pihak Sekutu (dalam hal ini Jenderal MacArthur dan Komando Mandala Pasifik Barat Daya yang dipimpinnya) memandang Hollandia sebagai batu loncatan strategis yang akan mendekatkan beliau dan tentaranya 800km ke sasaran utama di Filipina. Strategi lompat katak untuk merebut Hollandia juga berarti berperang di tempat yang dipilih AS, karena Jepang mengharapkan Sekutu mendarat diantara Madang dan Wewak, dimana Jepang menggelar tiga divisi infanteri dari AD #18 -yang otomatis terisolasi dengan pendaratan Hollandia-.

Kegagalan pihak Jepang tuk memprediksi serangan Sekutu ke Hollandia disebabkan perhitungan mereka bahwa Hollandia berada diluar jangkauan pesawat-pesawat tempur sekutu dari pengkalan terdepan mereka di Nieuw Guinea (Nadzab). Hal ini tentunya mudah diatasi Sekutu dengan memanfaatkan dukungan kapal-kapal induk dan pesawat-pesawat terbaru yang berjarak tempuh jauh. Namun demikian, perencana operasi memutuskan untuk menduduki juga Aitape karena disana terdapat lanud Tadji yang dapat digunakan sekutu, dengan mempertimbangkan Hollandia bakal dipertahankan mati-matian. Apalagi karena Jepang juga membangun 2 lanud di Wakde dan Sarmi, 200km lebih baratdaya Hollandia.

Target operasi:

Dalam serangan ke Hollandia, selain kota dan pelabuhan lautnya , yang menjadi sasaran utama Sekutu adalah tiga pangkalan udara di daerah Sentani, 40km di barat kota Hollandia, yang masing-masing disebut lanud Sentani, lanud Cyclops dan lanud Hollandia (lanud Tami, yang keempat, ada di dekat perbatasan RI-PNG sekarang). Sasaran-sasaran di Sentani ini direncanakan dijepit dengan penyerangan simultan melalui pendaratan amfibi dari dua arah, yaitu dari arah Teluk Humboldt (Teluk Yos Sudarso sekarang) dan Teluk Tanahmerah. Operasi militer dijadwalkan berlangsung pada 22 April 1944.

Kekuatan Sekutu.

Kekuatan udara dalam penyerangan ini adalah AU #5 AS, Gugus Tugas 73 (pesawat AL yang berpangkalan darat), komponen AU Australia, Gugus Tugas 78 (kapal-kapal induk pengawal dari Armada #7) dan Gugus Tugas 58 (kapal-kapal induk utama dari Armada #5, dipinjamkan oleh Laksamana Chester W. Nimitz, panglima Komando Mandala Samudra Pasifik ke MacArthur tuk serangan ini).

Armada laut sekutu dibagi dalam Gugus Tugas 77.1 (grup serbu tengah. Sasaran: Teluk Tanahmerah); Gugus Tugas 77.2 (grup serbu barat. Sasaran: Teluk Humboldt); Gugus Tugas 77.3 (grup serbu timur; Sasaran: Aitape); Gugus Tugas 74 (satuan pengawal A); Gugus Tugas 75 (satuan pengawal B) dan beberapa Gugus Tugas lain (77.4-7) yang berfungsi sebagai pasukan cadangan dan pengendali pendaratan. Bersama kapal-kapal induk, total Sekutu mengerahkan 217 kapal dalam misi ini.

Sebagai ujung tombak serangan ke Hollandia adalah Gugus Tugas Reckless: dua divisi infanteri dari Korps #1, AD #6 AS; Divisi Infantri #24 (sasaran Teluk Tanahmerah) dan Divisi Infanteri #41 (sasaran Teluk Humboldt); sementara Aitape akan diduduki oleh Gugus Tugas Persecution, yaitu Resimen Infanteri #163 dari Divif #41. Total semua pasukan darat berjumlah hampir 50.000 prajurit.

Dari H minus ke H plus.

Mulai akhir Maret, kekuatan udara Sekutu mengadakan pemboman berulang-ulang terhadap semua pangkalan udara dan laut Jepang di sepanjang pantai utara Papua, hingga laut Arafura, juga sampai ke Kep. Caroline dan Palau. Di Hollandia saja, serangan pendahuluan ini menghancurkan 300an pesawat Jepang per 3 April. Sementara itu, Sekutu terus menipu Jepang dengan berbagai taktik supaya Jepang tidak bisa memperkirakan dimana invasi berikutnya akan diarahkan.

Tanggal 17 dan 18 April 1944, konvoi kapal mulai bergerak dari pangkalannya masing-masing di ujung Nieuw Guinea. Dari Pulau Goodenough membawa Div #24, dan dari Tanjung Cretin membawa Div #41. Sementara Gugus Tugas Persecution berangkat dari Finschhafen. 20 April, konvoi menuju utara untuk memutar kepulauan Admiralties, supaya tidak terpantau dari garis pantai Teluk Hansa. Dari utara Admiralties konvoi langsung bergerak menuju sasaran. 12km dari pantai diantara Hollandia dan Aitape, grup serang timur memisahkan diri untuk mengeksekusi Operation Persecution.

Pada hari H 0130AM, 20 km dilepas pantai antara kedua teluk sasaran, konvoi yang tersisa memisahkan diri: grup serang tengah menuju Teluk Humboldt, sementara grup serang barat dan gugus tugas pasukan cadangan+mabes operasi menuju Teluk Tanahmerah. Pendaratan direncanakan serentak pada 0700 pagi sesudah serangkain bombardemen pantai, dan Operation Reckless resmi dimulai.

Di Teluk Tanahmerah, pendaratan dilakukan Divisi Infantri #24 pada dua lokasi yang bersandi Red Beach 1 dan 2. Karena memperhitungkan bahwa kekuatan utama Jepang akan terkonsentrasi mempertahankan Hollandia (yang diserbu dari Humboldt), maka pasukan pendarat terbesar, termasuk logistik dan para staf akan didaratkan disini. Tetapi kondisi di lapangan ternyata tidak sesuai dengan interpretasi foto udara para perencana operasi. Di Red Beach 2 tidak terdapat jalan ke Red Beach 1, sehingga pasukan, peralatan dan perbekalan yang menumpuk di pantai harus dibawa lagi dengan kapal-kapal kecil ke Red Beach 1.

LST di Red Beach 2

LST di Red Beach 2Sementara itu, dari Depapre (Red Beach 1) ke sasaran di Sentani ternyata hanya terdapat jalan setapak yang tak dapat dilalui kendaraan hingga jauh, bahkan oleh tank, tidak ada jalan buatan Jepang seperti yang diperkirakan. Oleh karena itu pasukan dari Div #24 harus bergerak maju dengan berjalan kaki saja, membawa logistik secara berantai. Sementara itu perbekalan, staf mabes (yang sebagian sudah turun), pasukan cadangan dan unit-unit pendukung yang masih di kapal dialihkan ke Teluk Humboldt. Begitu juga dengan status pasukan pemukul utama dialihkan ke Div #41 yang bergerak lebih lancar.

Pagi itu juga pasukan terdepan (Yon #1) sudah mencapai Maribu tanpa perlawanan, hanya ada sisa-sisa peralatan pasukan Jepang yang kabur. Selanjutnya menuju ke Paipou. Jangkena, Waibron, Dazai (Dosai sekarang) sebelum mencapai Sabron keesokan harinya. Di Sabron sempat ada perlawanan Jepang yang menahan pasukan hingga tanggal 23. Sementara batalyon #1 membuka jalan. Batalyon #2, #3 dan pasukan selebihnya disibukkan dengan membawa amunisi dan ransum secara berantai, berjalan kaki dari pantai sampai pasukan terdepan (sekitar 12 mil). Masalah logistik ini menghambat pergerakan pasukan hingga tanggal 25, karena semakin jauhnya jarak yang harus ditempuh untuk mengalirkan logistik ke pasukan yang juga semakin banyak, belum lagi hujan yang selalu turun. 25 April, dimana pasukan terdepan sempat mendapat perlawanan lagi di Sungai Dejaoe, sekitar 3500 pasukan sudah ditugaskan untuk hanya untuk membawa logistik saja. Meskipun dengan segala keterbatasan, hari esoknya (26), Yon #1 sudah berhasil menguasai lanud Hollandia, dan sebagian logistik berhasil diterjunkan menggunakan pesawat di Dazai. Sementara itu kendaraan dari kedua ujung juga sudah bisa melewati sebagian jalan. Hari itu juga, di sekitar Weversdorp, unit dari Div #24 sudah bisa mengadakan kontak dengan unit dari Div #41.

Pantai yang sangat sempit

Pantai yang sangat sempitDi Teluk Humboldt, pendaratan Div #41 dilakukan di empat lokasi yang diberi sandi White Beach 1-4. Disini juga pendaratan berjalan lancar dan hanya sedikit sekali mendapat perlawanan. Masalah yang dihadapi juga sama saja, yaitu pantai yang terlalu sempit untuk menampung segala muatan kapal-kapal pendarat, dan usaha keras membangun jalan dari pantai ke jalan raya Pim-Hollandia.

Sesegera semua pasukan mendarat, kedua resimen dari Div #41 berpencar. Resimen #162 bergerak menuju kota Hollandia, sementara Resimen #186 bergerak ke arah Sentani. Hari itu juga bukit Pancake dan bukit Jarremoh (kompleks pemancar Polimaq sekarang) bisa dikuasai, dan tanggal 23 siang, kota Hollandia sudah jatuh ke tangan pasukan AS.

Disisi lain, pasukan yang menuju Sentani mengalami sedikit hambatan karena hujan lebat yang membuat jalanan penuh kubangan, juga beberapa perlawanan sporadis dari pasukan Jepang. Pasukan AS juga sempat harus menghemat ransum dan amunisi karena pada tanggal 23 tengah malam, serangan tunggal pesawat tempur Jepang di White Beach 1 menimbulkan ledakan berantai yang menghancurkan 60% logistik dan amunisi AS hingga H+1.

Tanggal 24 sore, pasukan AS sudah menguasai dermaga alam kecil di Koyabu (Yoka) yang bisa digunakan untuk serangan amfibi. 25 pagi, 2 kompi dari Yon 1 memulai gerakan amfibi lewat danau Sentani menuju kampung Nefaar (Netar sekarang), disusul sisa Yon 1 pada siang harinya. 25 Sore, Yon 3 yang bergerak lewat darat (sisi danau Sentani) sudah bergabung. Tanggal 26 pagi, pasukan terdepan dibagi dua dan hari itu juga menguasai lanud Cyclops (jam 10.40) dan, setelah melewati kampung Ifaar, menguasai lanud Sentani (jam 11.30). Seluruh target dinyatakan aman sejam kemudian tanpa pertempuran berarti, dan ketika senja, sudah mampu mengadakan kontak dengan unit dari Divisi #21.

Setelah semua target utama operasi dinyatakan tercapai tanggal 26, operasi kemudian dilanjutkan dengan menguasai wilayah sekitar dan membersihkannya dari pasukan Jepang yang tersisa. Pada hari-hari berikutnya pasukan AS bergerak menguasai sisi selatan Gunung Cyclops (tempat markas Komando Mandala Pasifik BaratDaya kemudian dibangun), Tanjung Suaja (Tanjung Ria), Hollekang (Holtekamp sekarang), Goya (Koya) dan Tanjung Jar, lalu menguasai lanud Tami. Lanud ini kemudian sempat dipakai sebagai pangkalan jembatan udara tuk mengangkut logistik dari kapal menuju pasukan di wilayah Sentani yang kesulitan ransum. Pasukan AS juga menyebar dan membangun pos-pos hingga ke Marneda, Teluk Demta, bahkan Genyem. Acara “bersih-bersih” ini selesai per 6 Juni 1944.

Yang bertahan:

Diluar perkiraan sekutu, serangan ke Hollandia ternyata tidak mendapat perlawanan berarti dari pihak Jepang. Selain karena unsur kejutannya, hal ini juga disebabkan oleh terbatasnya waktu dan sumberdaya yang dimiliki Jepang untuk memindahkan elemen tempur darat yang signifikan ke Hollandia atau memperkuat pasukan yang sudah ada. Per 22 April 1944, dari sekitar 11.000 pasukan Jepang di Hollandia, hanya 500an saja pasukan darat dari unit anti serangan udara. Sisanya berasal dari pasukan udara, laut dan unit-unit pendukung lainnya.

22 April pagi, Mayjen Inada yang mengambilalih komando Jepang di Hollandia, menyusun perlawanan semampunya dan masih sempat mengkoordinasikan perlawanan di Sabron. Tetapi sebagian besar pasukannya segera kabur ke pegunungan sesaat setelah kapal-kapal AS melakukan bombardir, dan pada malam itu juga Mayjen Inada sudah memerintahkan mundur teratur. Tanpa perbekalan yang semuanya tersimpan di sekitar Teluk Humboldt, Jepang mundur ke arah Genyem, dimana mereka mengadakan proyek pertanian. Tanggal 30 April, sekitar 7000 tentara Jepang mengorganisasikan diri dalam 10 kelompok, tanpa peta dan perbekalan terbatas, memulai long march menuju Sarmi lewat jalan setapak di hutan; sebagian lagi ada yang ke Demta, desa pantai 25km di barat Depapre. Karena penyekatan pasukan AS, tersesat, kelaparan, luka, kelelahan dan penyakit, perjalanan ini menjadi mematikan, dan hanya sekitar 7% yang sampai di Sarmi. Secara total, hanya sekitar 1000an orang tentara Jepang yang selamat dari penyerbuan Hollandia. 3300an orang terbunuh atau ditemukan tewas, dan sisanya (hampir 7000) hilang. Di lain pihak, hanya 124 pasukan AS yang gugur, 1057 terluka dan 28 hilang.

Hollandia, sesudah invasi.

Sesudah invasi sukses, Sekutu kemudian membangun berbagai fasilitas militer, terutama bagi Armada Ketujuh, yang tersebar mulai dari Teluk Tanahmerah hingga Tanjung Suadja. Seluruh instalasi militer di Hollandia dan sekitarnya itu kemudian diberi kode alfabetik “Base G”.

Kesibukan tentara AS di pelabuhan yang sedang dibangun

Kesibukan tentara AS di pelabuhan yang sedang dibangunJend. D. MacArthur lalu memindahkan markas besar Komando Mandala Pasifik Baratdaya dari Brisbane ke Hollandia pada Agustus 1944, di sebuah bukit yang sekarang disebut Ifar Gunung, sekitar 4km diutara lanud Cyclops. Bersama mabes SWPA turut bermarkas di juga komando-komando dibawahnya a.l.: Armada #7, AD #6, AD #8, AU Sekutu dan Tentara Darat Sekutu.

Selanjutnya dalam perang, Hollandia kemudian menjadi titik awal bagi serbuan-serbuan Sekutu berikutnya ke P. Wakde, P. Biak, P. Numfor, Sansapor, dan P. Morotai, hingga pendaratan di P. Luzon, Filipina. Sementara itu AD #18 Jepang yang terkunci di sekitar Wewak akibat operasi ini, berhasil dikalahkan pada akhir Agustus.

Seusai perang.

Seiring dengan berakhirnya PD II, pada Desember 1945 AS menjual segala fasilitas militernya di Hollandia kepada pemerintah Hindia Belanda, yang lalu mewariskannya kepada pemerintah RI sesudah operasi Trikora (sesudah itu Hollandia dinamakan Soekarnopura, lalu Jayapura). Sebagian besar fasilitas militer yang dibangun pasukan MacArthur lalu jatuh ke tangan militer Indonesia, terutama ke Kodam XVII Trikora, termasuk kompleks mako MacArthur di Ifar Gunung, Sentani yang kini menjadi Resimen Induk Kodam (Rindam), dan instalasi Kodam di sekitar Kloofkamp, termasuk kompleks Kodam lama. Tempat pendaratan Sekutu di White Beach 1 & 2 menjadi kompleks perumahan AL, sementara Lanud Hollandia AFAIK dijadikan pangkalan AU di Jayapura (tanpa fasilitas penerbangan). Adapun pelabuhan Armada #7 dan lanud Sentani (bandar udara Sentani sekarang) difungsikan sebagai pintu gerbang umum masuk ke Jayapura. Ada juga bangunan-bangunan yang dikuasai sipil dan sudah beralih fungsi atau dirobohkan. Hanya lanud Cycloops yang tidak dapat saya pastikan lagi tempatnya. Walaupun ada tempat yang saya curigai berdasarkan perkiraan posisinya dari peta dan beberapa quonset hut -bangunan logam rakitan setengah silinder yang menjadi ciri khas konstruksi peninggalan korps zeni militer AS jaman PD II- didekat situ.

Akan halnya peninggalan bukan bangunan seperti bangkai-bangkai kendaraan militer yang begitu banyak terserak di sekitar lokasi pendaratan, sudah habis dijual sebagai besi tua oleh masyarakat lokal. Sementara sisa bom, mortir dan peluru yang tidak meledak saat serangan Sekutu, tak ada habis-habisnya ditemukan dan digunakan sebagai bahan baku bom ikan oleh masyarakat lokal. BTW, sebuah drum BBM supertebal peninggalan USAAF masih saya pakai sebagai drum air di rumah saya sekarang.

Encore:

Sebuah tugu di pantai Hamadi menandai peristiwa pendaratan Sekutu, sementara tugu lainnya di Abepantai menandai kedatangan pasukan Jepang 2 tahun sebelumnya. Keduanya, bersama puluhan quonset hut yang masih bertebaran di penjuru kota, dan Tugu MacArthur di kompleks Rindam, menjadi pengingat akan perang besar yang pernah melewati Jayapura, yang ceritanya makin samar dan terlupakan ini. Bahkan ada informasi resmi yang sesat pula! Jadi, mumpung belum ada perang lagi, mari kita rayakan hidup ini

2.Dai Nippon Occupation Sumatera under the command from Singapore(syonato) Dai Nippon Military administration (Gunseikanbu) Malaya .(from march 192=42 until march,1st 1943,after that the command at BukittinggI,except Riau Island still under Singapore)

(1) Pictures Collections

a.DAI NIPPON POSTER AT JAVA 1942

(2) Postal History Collections

Due to diffucty of trasporatation and communicatiobs, each the command of each area issued their own overprint to the Dutch Queen (kon.) stamps and also numeric and dancer stamps.

Sumatra under Dai Nippon center Singapore)

Dai Nippon Bold west sumatra Dai nippon Yubin overpint lettersheet 71/2 cent (restored) 23.12.1944. Japan homeland definitif stamp used at Batusangkar west sumatra. 6.10.1944 Dai nippon poostcard stationer 31/2 cent send from padang to Painan Rejoined middle sumatra dai Nippon cross overprint oh the photocopy of Didik coolection Postally used cover from Pakanbaru to Syonato(Singapore) return to sender because the written language forbidden. The photocopy of ex Dr iwan s. collection : Straits 1 cent overprint Dai Nippon single frame (type 2) cds Padang 5.2.1943, during under Singapore Dai nippn military administration. 8.12.1943.Rejoined Middle sumatra Dai Nippon yubin and cross overprin on the photocopy of postally used cove send from pajakumbuh to Padang rejoined oc Dai nippon Yubin overprin on Karbou Kriesrler stamp with the photocopy one.send from West sumatra Resident to ChicoSaibancho Boekittinggi, below wrong info sent from padang Pandjang to Solo. Rejoined fragment with photocopy, Japan postcard stationer 2c with DN overprint 1 1/2 cent used at Bukittinggi fromm Resident west sumatra padang to chicko Sai bancho Boekittinggi

- 2.3.1943. palembang Dai Nippon square overprint, used CDS 18.3.2,this time sumatra still under Singapore Dai nippon Military adminsitration, al Sumatra area had got permission to overprint the Dutch East Indie stamps with Ryal Head picture, but also the other deffinitive,but different in Java no emergency ovpt because different military administration.

- Dai Nippon Postmaster Initial overprint on DEI Kon 10 cent, IPL(I.Piet lengkong) postmaster palembang first from his sihnet ring and hthen five type of IPL , the other Post office also issue the Ring signet or handsign overprint from all post office at south Sumatra-look at Dainippon occupation Sumatra catalogue, the guinined overprint very rare on postally used cover (please report)

2. Eastren Area Of Indonesia Under dai Nippon Naval Administration,

center at Macasar South Celebes)

(1) Pictures Collections

(2)Postal History Collections

(a) Borneo

(a1) West Borneo :

Pontianak

Pemangkat

Other city

(a2) South Borneo :

Banjarmasin

Other City

(a3) East Borneo :

Balikpapan

Samarinda

Tarakan

other city

(b) Celebes:

(b1)Macassar

(b2)Manado

(c) Molluca

(1) Ambon

(2) other area

(d) Small Sunda Island (Bali and Nusatenggara)

(d1) Bali

(d2) Ampenan

(d3 )other area.

3.The Dai Nippon Occupation Java postal and Documen History 1945(March ,8th until Dec.31th 1945-2605 Dai nippon Year)

Prolog

1.January 1942

On the 10th of January 1942, the Japanese invaded the Dutch East Indies. The newspapers brought us a lot of bad news. My father had long ago advised me to read some of the articles I liked from the Malanger and the Javabode starting since I was almost eleven years old, so now I could read all the bad news in the papers when I was at our Sumber Sewu, plantation home near the East Java city of Malang during the weekends.

Now and then we saw Japanese planes flying over Java. I found it all strange and very unreal. The only Japanese I knew where those living in Malang; they were always very polite and friendly towards us. But from now on Japan was our enemy.(true story By Elma)

2.February 1942

(1)February,12th.1942.

The Battle Of Palembang

The Dai Nippon paratroops army by parachute landed at Palembang and the oil area at plaju near Palembang were attack and occupied ,look the pictures.

(2)FEBRUARY,14TH,1942

On Saturday the 14th of February 1942,

my father came to fetch Henny (my younger sister) and I from our boarding-school for the weekend. We went into town where we did some shopping for my mother and next we went to the Javasche Bank. When my father came out of the bank, we heard and then saw Japanese planes coming over. This time they machine-gunned Malang. I saw two working men, who were hit, falling from the roof where they were busy. They were dead, we saw them lying in their blood on the street. I had never seen dead people before; Henny and I were deeply shocked. Henny started crying, my father took us both quickly away from this very sad sight.

(3)FEBRUARY,15TH. 1942

On Sunday the 15th of February we received the bad news over the radio that Singapore had fallen into Japanese hands. Indeed, that was a very sad Sunday. Who had ever thought that Singapore could fall? Were the Japanese so much stronger than the Allies? And then there was the Battle of the Java Sea from 27 February to 1 March 1942. The Dutch warships Ruyter and Java were hit by Japanese torpedoes; they sunk with a huge loss of life. The Allies lost this battle. The 8th of March 1942, the Dutch Army on Java surrendered to the Japanese Army.

..

.Jungle and Indian Ocean

Soon it was the New Year. We had no more Japanese visitors. There were not many Dutch or other Europeans outside of camps. In Malang there was already a camp for men called Marine Camp. And another camp, we were told, called De Wijk, prepared to house women and children. Taking a long, last walk through the rubber plantations and jungle, my father and I beheld the Indian Ocean. My father looked at me and said, “I have to ask you something, you are almost 16 so you are old enough. I want you to look after Mama and your sisters when I have to leave Sumber Sewa. Will you promise me that?” I remonstrated, but he insisted and I agreed.

And so, at the beginning of February 1942, my father received a phone call ordering him to leave our home in Sumber Sewu within six days and report to the Marine Camp in Malang. This would be a fateful separation. By now, most Dutch men were internees.

A Japanese visitor

(1)March,3th,1942

THE DAI NIPPON MILITARY OCCUPATION IN INDONESIA COLLECTION

1.MARCH 1st 2002

(1) Early in the morning this day, Dai Nippon forces landing in Java and succeeded withou any struggle by DEI forces(KNIL) and Indonesia Native people accepted DN Frces with up the DN and Indnesian national flag because Dai Nippon propaganda before the war that Indonesia will Independent when they occupied Indonesia,

Three Dai Nippon Forces Landing area in Java:

(a) Banten Beach at Merak with route Merak-Serang-Rangkasbitung-Leuwiliang-Buitenzorg(Bogor)-Kragilan-Tanggerang-Batavia under the command of the commander-in-chief 16th Dai Nippon forces Lt.Gen.Hitoshi Immamura, with the 2nd Division under Commander May.Gen. Maruyama, and the 49th Division under Commander May.Gen Tsuchi Hashi , also Brigade under commander May gen.

Sakaguchi and one Resimen under commander Col, Shoji.

Three Illustrations:

(ill.1) Gen.Immamura profile

(ill.2) Dai Nippon Landing

(1ll.3) The Vintage Dutch Map of Banten 1942: Merak beach landing area, and the route attack Searanf-Rangkasbitung,Leiwilliang Buitenzorg, Tanggerang- Batavia.

Caption : DN route map Banten 1942

(b) Eretan Wetan near Indramajoe

(ill 4) The Vintage Dutch Map of Indramjoe Dai Nippon landing area 1942,caption Indramajoe map 1942

(c) Krangan Rembang middle Java,

The fleet of Dai Nippon Naval Forces reach the Krangan coast ,a village between Rembang and Lasem, about 160 km west of Soerabaja.

The Sakaguchi detachment from Balikpapan joined this invasion fleet. After landing divided into 3 units with 1 battalion of 124th Infantry Regiment :

(c.1) Col.Yamamoto,1st Battalion unit.

(c.2) Mayor Kaneuji, 2nd Battalion unit.

(c.3) Let.Col.Matsimoto,3rd battalion unit.

In one week ,they advanced rapidly and overcome all Dutch army defended in Blora ,Solo ,Bojolali-Yogja ,Magelang and Ambarawa

the Map will illustrated

(2) All of the West Java Postal office were closed not opretated inculding Tjiandjoer.

(1ll.5) Postally free postally used Geadvisers (Registered) cover with Commander of the forces and the Departmen of War’s chief (Commandant Leger en hoofd departement van Oorlog ) official Headquaters Stamped send from The Dutch East Indie Forces Head Quaters Bandoeng CDS Bandoeng Riaow Str 27.2.42, arrival Cds Tjiandjoer 28.2.42 and after that the post office closed, open after capitulaition CDS Tjiandjoer 4.4.42 Onafgeh. and ret.afzd handwritten postmark (Cann’t delivered and return to sender) , arrived back CDS Bandoeng 6.4.42 (during dai nippon occupation0 to Dai Nippon Forces Headquaters in java .(The very rare Dai Nippon capitulation Postal History collection from the DEI forces headquaters back to Dai nippon forces Bandoeng Headquaters only one ever seen, if the collecters have the same collectins please send information via comment-Dr iwan S.)

Caption : capitulation cover 1942

(3) DEI Marine Defendwork Offive Letter during DN landing at west and Central Java.

Veryrare Letter from Marine Defensiewerk (Defense Worl office) sign by the chief van Schooninveld. the conduete latter of B Kasiman who work as opzichert (civilian official) at the Soerabaya Marine office from Augist 1941 to March 1942, the letter date April 1st 1942.

(Ill.6) The DEI Marine Soerabaya letter during DN landing west java, caption DEI Marine letter 1942

Dai Nippon Army Landed at Merak, and other area

(2)March,5th.1942 Batavia(Jakarta) occupied by dai Nippon Army lead by Let.General Immamura

A Japanese soldier outside oil tanks near Jakarta destroyed by Dutch forces in March,5th. 1942

(3)MARCH ,9th.1942.

The 9th of March, when we were in the recreation-room from our boarding-school while all the girls were looking through the windows into the streets, the Japanese entered Malang. Henny and I stood there together.

They came on bicycles or were just walking. They looked terrible, all with some cloth attached at the back of their caps, they looked very strange to us. This was a type of Japanese we had never seen before. Much later I learnt that many Koreans also served as shock-troops in the Japanese Army.

The nuns went to the chapel to pray for all those living in the Dutch East Indies. But the Dutch East Indies is lost forever.

Dutch a forbidden language

My father found it too dangerous for my mother and youngest sister Jansje to stay with him at Sumber Sewu, because there were still small groups of Australian, English and Dutch military fighting in the mountains in East Java against the Japanese troops, notwithstanding the fact that the Dutch East Indies government and Army had surrendered.

My mother and Jansje came to stay at our boarding school [at Malang], where there were small guest rooms. We all stayed inside the building, only the Indonesians working for the nuns went outside to do the shopping.

A few days later we received the order that all Dutch schools had to be closed down, so several parents came to take their daughters. The school looked empty and abandoned. We all felt very sad, our happy schooldays were over.

Dutch became a strictly forbidden language. Luckily we had a huge library at school so I had lots of books to read in those days.

A few weeks later my father phoned my mother and said that the four of us should return to Sumber Sewu as he had heard that Malang was no longer a safe place for us to stay.

I was really very happy to be back home. Rasmina, our cook, and Pa Min, our gardener, were happy to have my mother back again. There was absolutely nothing to fear on the plantation, the “Indonesians” (actually Javanese and Madurese) on the plantation were nice as ever and we didn’t see any Japanese soldiers around.

Indeed we were safer at Sumber Sewu. Life began to feel like a vacation,

I started walking with my father again and visited the local kampung (village) and since we had no more newspapers to read, I started reading several of my parent’s books.

We received a Japanese flag, together with the order that the flag had to be respected and had to hang in the garden in front of our house.

My father no longer received his salary, just like all the other Dutch, British, Americans and Australians, living in Indonesia. All our bank accounts were blocked; no one was even allowed to touch their own money.

We still had rabbits and eggs to eat, and several vegetables my mother and Pa Min had planted long before the war in the kitchen garden, and we had many fruit trees.

The thought that we might have to leave Sumber Sewu made me feel very sad. To me this plantation was a real paradise on earth, with its pond in front of the house with the two proud banyan trees, the lovely garden my mother and Pa Min had made, the kitchen where Rasmina made so many delicious meals. The sounds early in the morning, and the sounds in the evening were also very special, I can still remember them so well.

Of course we hoped that this Japanese occupation would soon be over. My father had broken the seal of the radio, hoping that he could get some more news from outside Java.

My mother and her three daughters.

(4)

In this month all the post office in Java not operational the letter send from Bandung February 17 1942 to Tjiandjoer arrived in february,28th,but cannot bring to sender because of the Dai nippon landed at Merak and marching to Jakarta (batavia) March,5th and capitulation Kalidjati Armyport March,8th 1942. this letter send to sender but cannot found and the sletter send back to sender April, 4th 1942 . Please look carefully this very rare historic postal used cover from DEI Armed forces Headquater Bandung official free stamp covers and return back to Dai Nippon Occupation Military Headquater Bandung below

front

back

2)March,8th 1942 Capitulation Dai nippon at Kalidjati military airport, The Dutch Armed Forces surrender (1) The House of capitulation’s Meeting now

(a) Interior still same meubeleur

(b)Exterior

(2)The Position of the capitulations meeting participant.

(c)The Original Photos

Let General Hitoshi Immamura the command of Dai nippon Army

had the cpitulation Meeting at kalidjati army port March 7th at night ,Immamura didnot want to meet with the ex DEI Govenorgeneral Tjarda

and the meeting only with the command od DEI Army General Ter Porten and Kastaf Col Bakkers

, and DEI Army surrender which announced at the newpaper morning March,8th, and the second meeting at Kalidjati 10 am with bring the list of DEI army powers. Immamura write in his memoir that they have sign the capitulation acta which never seen anymore (lost), after meeting they made a photo in the front of the meeting house which still exist now with the same meubelueur. look the photos below.

(c1) Interior

(c2) exterior

very difficult to find the original clear photos of the kalidjati capitulation meeting, all the pictures were taken by Dr Huesein at the location now which given to me not so clear, who have the original clear photos please show us.

2.April 1942

1)except Surabaya the DEI Govement still operation :

(1)The DEI marine still issued the recomendations letter

(2)the PTT still issued the telephone bill for april 1942.look below at April collectionsApril.1st 1945 .Surabaja.Ned.indie.Revenue stamp .PTT Phone Bill.

a.Front

b. back

(2) April,3rd1942,soerabaja,Recieved Of Buying Breadpaper, DEI Revenue stamped

(4) April,14th 1942,the DEI overtoon document (Surat hutang) handwritten sur charge to Indonesia Language ,the DEI change to Pemerintah balatentara Dai Nippon(DN army Government)

3.May 1942(1942)

(1) May,3th.1942, Koedoes,Recieved of Dai Nippon Postal saving bank(Chokin kyoku ) with the chokin label and book

(2)May,14th 1942 ,Sitoebondo,Legalization of Radio Permit of DEI 1941 document with DEI revenue that time,no Dai Nippon special revenue (all the radio band were closed only open for Dai nippon channel only)

Inside

Frontside

Legalized DEI C7 Adress card with Kon stamp 10 cent issued at Batoe Malang east java ,by Dai nippon in Indonesia language with handwritten

Beside the road in jakarta,dai nippon put their propaganda radio on the pole,look the book illustration from magazine july 2602

4. June 2602(1) June 11th 2602 DEI Postal stationer CDS Bandoeng send to Semarang.(all DEI postal issued without Queen Wilhelmina picture permit to used without overprint in Java.This is the earliest postal stationer card used during Dai Nippon Occupation Java.

5.July 2602

(1) july,7th 2602 billing recieved, DEI Revenue,and Dai nippon Calender date 2602

(2)July,11th 2602, The Dai nippon Liscence to print a book at the front page

6.August 2602

on the 11th of August in , that I read in the Dutch newspaper, De Telegraaf, that many more people had seen what my father and I witnessed that day in 1942. Other people had seen many of these men transported in bamboo baskets not only in trucks but also in trains. The article said that the men had been pushed into the bamboo baskets, transported, and then, while still in those baskets, thrown into the Java Sea. Most of the men in the bamboo baskets were Australian military.

I have often wondered: Did my father learn what happened to those poor men we saw that day? Did the local people see it as well? I shall never know.

Come! Let’s walk home

It was strange that we didn’t get Japanese military visitors at Sumber Sewu since they went to Wonokerto the head plantation and other plantations as well, and asked many questions there. My parents were of course more than pleased that the Japanese hadn’t visited Sumber Sewu yet

7.September 2602The first Dai nippon 2602 Zegel van Ned indie Imprint used adi nippon year but still used the same imprint zegel of DEI emblem, used at Magelang Polytechnic middle school certificate

8.October 1942

(1)one day at the end of October 1942, when my father and I walked back home for lunch, we heard a lot of noise. It was the sound of trucks coming in our direction as we were walking on a main road. So we quickly walked off the road and hid behind some coffee bushes. We saw five trucks coming and we heard people screaming. When the trucks passed we could see and hear everything, especially since we were sitting higher than the road. What we saw came as a real shock to both of us.

We saw that the open truck platforms were loaded with bamboo baskets, a type of basket used to transport pigs. But the bamboo baskets we saw that day were not used for pigs but for men. They were lying crammed in those baskets, all piled up three to four layers of baskets high. This sight shocked us deeply, but the screaming of all those poor men, for help and for water, in English and Dutch, shocked us even more. I heard my father softly saying; “Oh my God?”

We walked home without saying a word. We had just come out of a nightmare. Even today I can still hear the harsh voices of these poor men crying and screaming for help and for water.

At lunch time my father told my mother the whole story — she could hardly believe that people could do such things. She asked who were driving the trucks. My father told her that in each truck he had seen a Japanese driver and another Japanese sitting next to them.

This tragedy that I saw together with my father happened in the mountains of East Java.

(2)October 26th 2602(1942)

Tamanan Gun Cho(Tamanan was an area at East java -military Command),used DEI postal Stationer because this time Dai Nippon Military Postalcard not exist.

9.November 2602

(1)one day in November 1942 my parents received a phone call from the police in nearby Ampelgading. My father had to bring his car to the police station. It was summarily confiscated. Still, he was happy to have my company on this very difficult afternoon. We went by car but– a real humiliation – we had to walk back home.

When my father came back from work, he said that he really hoped that the Americans and Aussies would come soon to rescue us all from this Japanese occupation of Indonesia. Many Dutch civilian men were now interned all over Java, but not only men, as the Japanese had also started to open camps for women with their children as well.

We were still “free” but for how long?

(2) November,9th 2602.Solo, the earliest Dai Nippon Plakzegel revenue Stamped.

10.December 2602

(1) December,25th.1942

Christmas 1942

My mother did her utmost in the kitchen to prepare a nice Christmas meal. And then at last it was the 25th of December, 1942. It must have been around 12 noon when we started our delicious Christmas meal, sitting there all six happy around the table.

All of a sudden we heard Pa Min calling; “Orang Nippon, orang Nippon.” (lit. Japanese). My father stood up and went to the front door, my mother took little Jansje by her hand and they went to the living room. Cora went to our bedroom with a book; she was very scared. Henny and I stood at the back of the house and so we could see that there were about six or seven Japanese military getting out of two cars. One of them was an officer. Directly approaching my father, he said that his men had received an order to search the house for weapons. My father told him that there were no weapons hidden in the house.

It was our last Christmas as a whole family together. I can still feel the special warmth of that gathering we had that day because, notwithstanding the Japanese military visit, we were still together

(2)December,31th 2602.

the document of Dai Nippon lend the Car

1)original document

2) translate of the document

1943

1.February.12th.03(1943),Toemenggoeng Official Military red Handchopped(unidentified)

Bab Tiga(Chapter Three):

The Dai nippon Military Java Postal History

1.October 26th 2602(1942),Tamanan Gun Cho(Tamanan was an area at East java -military Command),used DEI postal Stationer because this time Dai Nippon Military Postalcard not exist.

2.February.12th.03(1943),Toemenggoeng Official Military red Handchopped(unidentified)

3.Military Postcard send via military courier from Magelang to Djatinegara.Read the translate .

Rare Dai Nippon Guntjo Pos Losarang with house of delivery(Rumah Pos) Stamped on postal stationer card 2603(1943)

Semarang Kezeibu Official CDS Semarang 27.12.03 card to Kudus

Frontside

Backside

Tekisan Kanribu(Dai Nippon Enemy Property Control) Bandung official Postal Used lettersheet homemade ,4.9.03(Sept.4th,1943)

C.Occupation

Bab Empat(Chapter Four);

.The History of Japanese occupation Indonesia

| This article is part of the History of Indonesia series |

|---|

|

| See also: Timeline of Indonesian History |

| Prehistory |

| Early kingdoms |

| Kutai (4th century) |

| Tarumanagara (358–669) |

| Kalingga (6th to 7th century) |

| Srivijaya (7th to 13th centuries) |

| Sailendra (8th to 9th centuries) |

| Sunda Kingdom (669–1579) |

| Medang Kingdom (752–1045) |

| Kediri (1045–1221) |

| Singhasari (1222–1292) |

| Majapahit (1293–1500) |

| The rise of Muslim states |

| Spread of Islam (1200–1600) |

| Sultanate of Ternate (1257–present) |

| Malacca Sultanate (1400–1511) |

| Sultanate of Demak (1475–1548) |

| Aceh Sultanate (1496–1903) |

| Sultanate of Banten (1526–1813) |

| Mataram Sultanate (1500s–1700s) |

| European colonialism |

| The Portuguese (1512–1850) |

| Dutch East India Co. (1602–1800) |

| Dutch East Indies (1800–1942) |

| The emergence of Indonesia |

| National awakening (1899–1942) |

| Japanese occupation (1942–1945) |

| National revolution (1945–1950) |

| Independent Indonesia |

| Liberal democracy (1950–1957) |

| Guided Democracy (1957–1965) |

| Start of the New Order (1965–1966) |

| The New Order (1966–1998) |

| Reformasi era (1998–present) |

| v · d · e |

The Japanese Empire occupied Indonesia during World War II from March 1942 until after the end of War in 1945. The period was one of the most critical in Indonesian history.

The occupation was the first serious challenge to the Dutch in Indonesia—it ended the Dutch colonial rule—and, by its end, changes were so numerous and extraordinary that the subsequent watershed, the Indonesia Revolution, was possible in a manner unfeasible just three years earlier.[1] Under German occupation itself, the Netherlands had little ability to defend its colony against the Japanese army, and less than three months after the first attacks on Borneo the Japanese navy and army overran Dutch and allied forces, ending over 300 years of Dutch colonial presence in Indonesia. In 1944–45, Allied troops largely by-passed Indonesia and did not fight their way into the most populous parts such as Java and Sumatra. As such, most of Indonesia was still under Japanese occupation at the time of their surrender in August 1945.

The most lasting and profound effects of the occupation were, however, on the Indonesian people. Initially, most had optimistically and even joyfully welcomed the Japanese as liberators from their Dutch colonial masters. This sentiment quickly changed as the occupation turned out to be the most oppressive and ruinous colonial regime in Indonesian history. As a consequence, Indonesians were for the first time politicised down to the village level. But this political wakening was also partly due to Japanese design; particularly in Java and to a lesser extent Sumatra, the Japanese educated, trained and armed many young Indonesians and gave their nationalist leaders a political voice. Thus through both the destruction of the Dutch colonial regime and the facilitation of Indonesian nationalism, the Japanese occupation created the conditions for a claim of Indonesian independence. Following World War II, Indonesians pursued a bitter five-year diplomatic, military and social struggle before securing that independence.

Contents

|

Background

Until 1942, Indonesia was colonised by the Netherlands and was known as the Netherlands East Indies. In 1929, during the Indonesian National Awakening, Indonesian nationalists leaders Sukarno and Mohammad Hatta (later founding President and Vice President), foresaw a Pacific War and that a Japanese advance on Indonesia might be advantageous for the independence cause.[2]

The Japanese spread the word that they were the ‘Light of Asia’. Japan was the only Asian nation that had successfully transformed itself into a modern technological society at the end of the nineteenth century and it remained independent when most Asian countries had been under European or American power, and had beaten a European power, Russia, in war.[3] Following its military campaign in China Japan turned its attention to Southeast Asia advocating to other Asians a ‘Greater East Asian Co-Prosperity Sphere’, which they described as a type of trade zone under Japanese leadership. The Japanese had gradually spread their influence through Asia in the first half of the twentieth century and during the 1920s and 1930s had established business links in the Indies. These ranged from small town barbers, photographic studios and salesmen, to large department stores and firms such as Suzuki and Mitsubishi becoming involved in the sugar trade.[4] The Japanese population peaked in 1931, with 6,949 residents before starting a gradual decrease, largely due to economic tensions between Japan and the Netherlands Indies government.[5] Japanese aggression in Manchuria and China in the late 1930s caused anxiety amongst the Chinese in Indonesia who set up funds to support the anti-Japanese effort. Dutch intelligence services also monitored Japanese living in Indonesia.[6] A number of Japanese had been sent by their government to establish links with Indonesian nationalists, particularly with Muslim parties, while Indonesian nationalists were sponsored to visit Japan. Such encouragement of Indonesian nationalism was part of a broader Japanese plan for an ‘Asia for the Asians’.[7]

In November 1941, Madjlis Rakjat Indonesia, an Indonesian organization of religious, political and trade union groups, submitted a memorandum to the Dutch East Indies Government requesting the mobilization of the Indonesian people in the face of the war threat.[8] The memorandum was refused because the Government did not consider the Madjlis Rakyat Indonesia to be representative of the people. Within only four months, the Japanese had occupied the archipelago.

The Invasion

On December 8, 1941, Netherlands declared war on Japan.[9] In January the American-British-Dutch-Australian Command (ABDACOM) was formed to co-ordinate Allied forces in South East Asia. On the night of January 10–11, 1942, the Japanese attacked Menado in Sulawesi. At about the same moment they attacked Tarakan, a major oil extraction centre and port in the north east of Borneo. On February 27, the Allied fleet was defeated in the Battle of the Java Sea. From February 28 to March 1, 1942, Japanese troops landed on four places along the northern coast of Java almost undisturbed. On March 8, the Allied forces in Indonesia surrendered. The colonial army was consigned to detention camps and Indonesian soldiers were released. European civilians were interned once Japanese or Indonesian replacements could be found for senior and technical positions.[10]

Liberation from the Dutch was initially greeted with optimistic enthusiasm by Indonesians who came to meet the Japanese army waving flags and shouting support such as “Japan is our older brother” and “banzai Dai Nippon“.

The Indonesians abandoned their colonial masters in droves and openly welcomed the Japanese as liberators. As the Japanese advanced, rebellious Indonesians in virtually every part of the archipelago killed small groups of Europeans (particularly the Dutch) and informed the Japanese reliably on the whereabouts of larger groups[11]

In Aceh, the local population rebelled against the Dutch colonial authorities, even before the arrival of the Japanese. As renowned Indonesian writer Pramoedya Ananta Toer noted:

With the arrival of the Japanese just about everyone was full of hope, except for those who had worked in the service of the Dutch.[12]

The occupation

Indonesia under the Japanese occupation [13]

Initially Japanese occupation was welcomed by the Indonesians as liberators.[14] During the occupation, the Indonesian nationalist movement increased in popularity. In July 1942, leading nationalists like Sukarno accepted Japan’s offer to rally the public in support of the Japanese war effort. Both Sukarno and Mohammad Hatta were decorated by the Emperor of Japan in 1943.

Japanese rulers divided Indonesia into three regions; Sumatra was placed under the 25th Army, Java and Madura were under the 16th Army, while Borneo and eastern Indonesia were controlled by the Navy 2nd South Fleet. The 16th and 25th Army were headquartered in Singapore[1] and also controlled Malaya until April 1943, when its command was narrowed to just Sumatra and the headquarters moved to Bukittinggi. The 16th Army was headquartered in Jakarta, while the 2nd South Fleet was headquartered in Makassar.

Experience of the Japanese occupation of Indonesia varied considerably, depending upon where one lived and one’s social position. Many who lived in areas considered important to the war effort experienced torture, sex slavery, arbitrary arrest and execution, and other war crimes. Many thousands of people were taken away from Indonesia as unfree labour (romusha) for Japanese military projects, including the Burma-Siam Railway, and suffered or died as a result of ill-treatment and starvation. People of Dutch and mixed Dutch-Indonesian descent were particular targets of the Japanese occupation and were interned.

During the World War II occupation, tens of thousands of Indonesians were to starve, work as slave labourers, or be forced from their homes. In the National Revolution that followed, tens, even hundreds, of thousands (including civilians), would die in fighting against the Japanese, Allied forces, and other Indonesians, before Independence was achieved.[15] A later United Nations report stated that four million people died in Indonesia as a result of famine and forced labor during the Japanese occupation, including 30,000 European civilian internee deaths.[16]

Netherlands Indian roepiah – the Japanese occupation currency

Materially, whole railway lines, railway rolling stock, and industrial plants in Java were appropriated and shipped back to Japan and Manchuria. British intelligence reports during the occupation noted significant removals of any materials that could be used in the war effort.

The only prominent opposition politician was leftist Amir Sjarifuddin who was given 25,000 guilders by the Dutch in early 1942 to organise an underground resistance through his Marxist and nationalist connections. The Japanese arrested Amir in 1943, and he only escaped execution following intervention from Sukarno, whose popularity in Indonesia and hence importance to the war effort was recognised by the Japanese. Apart from Amir’s Surabaya-based group, the most active pro-Allied activities were among the Chinese, Ambonese, and Menadonese.[17]

Indonesian nationalism

During the occupation, the Japanese encouraged and backed Indonesian nationalistic feeling, created new Indonesian institutions, and promoted nationalist leaders such as Sukarno. In the decades before the war, the Dutch had been overwhelmingly successful in suppressing the small nationalist movement in Indonesia such that the Japanese proved fundamental for coming Indonesian independence.[15]

The Japanese regime perceived Java as the most politically sophisticated but economically the least important area; its people were Japan’s main resource. As such—and in contrast to Dutch suppression—the Japanese encouraged Indonesian nationalism in Java and thus increased its political sophistication (similar encouragement of nationalism in strategic resource-rich Sumatra came later, but only after it was clear the Japanese would lose the war). The outer islands under naval control, however, were regarded as politically backward but economically vital for the Japanese war effort, and these regions were governed the most oppressively of all. These experiences and subsequent differences in nationalistic politicisation would have profound impacts on the course of the Indonesian Revolution in the years immediately following independence (1945–1950).

In addition to new-found Indonesian nationalism, equally important for the coming independence struggle and internal revolution was the Japanese orchestrated economic, political and social dismantling and destruction of the Dutch colonial state.[15]

End of the occupation

General MacArthur had wanted to fight his way with Allied troops to liberate Java in 1944-45 but was ordered not to by the joint chiefs and President Roosevelt. The Japanese occupation thus officially ended with Japanese surrender in the Pacific and two days later Sukarno declared Indonesian Independence. However Indonesian forces would have to spend the next four years fighting the Dutch for its independence. American restraint from fighting their way into Java certainly saved many Japanese, Javanese, Dutch and American lives. On the other hand, Indonesian independence would have likely been achieved more swiftly and smoothly had MacArthur had his way and American troops occupied Java.[18]

Liberation of the internment camps holding western prisoners was not swift. Sukarno, who had Japanese political sponsorship starting in 1929 and continuing into Japanese occupation, convinced his countrymen that these prisoners were a threat to Indonesia’s independence movement. Largely because they were political bargaining chips with which to deal with the colonizer, but also largely to humiliate them; Sukarno forced Westerners back into Japanese concentration camps, still run by armed Japanese soldiers. While there certainly was enough labor to garrison these camps with Indonesian soldiers, Sukarno chose to allow his former ally to maintain authority. Conditions were better during post war internment than under previous internment, this time Red Cross supplies were made available and the Allies made the Japanese order the most heinous and cruel occupiers home. After four months of post war internment Western internees were released on the condition they leave Indonesia.

Most of the Japanese military personnel and civilian colonial administrators were repatriated to Japan following the war, except for several hundred who were detained for investigations into war crimes, for which some were later put on trial. About 1,000 Japanese soldiers deserted from their units and assimilated into local communities. Many of these soldiers provided assistance to rebel forces during the Indonesian National Revolution.[19]

The first stages of warfare were initiated in October 1945 when, in accordance with the terms of their surrender, the Japanese tried to re-establish the authority they relinquished to Indonesians in the towns and cities. Japanese military police killed Republican pemuda in Pekalongan (Central Java) on 3 October, and Japanese troops drove Republican pemuda out of Bandung in West Java and handed the city to the British, but the fiercest fighting involving the Japanese was in Semarang. On 14 October, British forces began to occupy the city. Retreating Republican forces retaliated by killing between 130 and 300 Japanese prisoners they were holding. Five hundred Japanese and 2000 Indonesians had been killed and the Japanese had almost captured the city six days later when British forces arrived

________________________________________________________________

The official Office Stamped during Dai nippon War In Java(restored)

1. Official Keraton Jogya

2.Dai Nippon Kanji Choped(?)

3.Postal Saving Office

4.Madioen Student(Pelajar)

5.District Karangan

6.chief of village

PSThe Dai Nippon Occupation postal and document history from other time and area In Indonesia only for Premium Member,please subscribe via comment, and we will tell you the regulations via your e.mail adress.this improtant for security the web blog.

the end @ copyright Dr Iwan suwandy 2011

![The Battle for Okinawa [Light]](https://i0.wp.com/library.thinkquest.org/19981/images/messages/7-2.jpg)

Can Tho Ancient Market

Can Tho Ancient Market Vom Market

Vom Market Ninh Kieu QuayCan Tho is a regional cultural hub characterized by unique agricultural traits of the Southern farmers practicing wet rice plantation. Can Tho has specific streghths for tourism developement not only in a quite complete infrastructure but also in rich and diverse tourism potentials. Can Tho has been striving for a modern city im bued with benevolence and marked by the Mekong Delta’s special features that promises to become the nation’s most attractive river and countryside – based eco – tourist destination.

Ninh Kieu QuayCan Tho is a regional cultural hub characterized by unique agricultural traits of the Southern farmers practicing wet rice plantation. Can Tho has specific streghths for tourism developement not only in a quite complete infrastructure but also in rich and diverse tourism potentials. Can Tho has been striving for a modern city im bued with benevolence and marked by the Mekong Delta’s special features that promises to become the nation’s most attractive river and countryside – based eco – tourist destination.